Today the UK enters its sixth week of what is being termed “lockdown”, although that term to my mind over dramatises the situation as the restrictions, whilst they have a basis in law (The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) Regulations 2020 and corresponding legislation in Wales and Scotland), are being enforced primarily through a combination of personal behaviour change reinforced by peer pressure, and relatively light-touch policing rather than by troops on the streets and checkpoints with uniformed officials demanding “papers please”. Whatever we call it, the past six weeks and the threat that hangs over them have had a profound impact on our national psyche.

Following a burst of panic buying in the early stages, primarily it seemed of pasta and toilet rolls, when retailers and their supply chains struggled to keep up, life in Lockdown Britain seems to have adjusted remarkably quickly and smoothly to the new normal. Of course, the impacts are not shared evenly by everyone, no matter how much it might seem that this time we really are all in it together. The experience in affluent commuter villages where furloughed executives enjoy 6pm “quarantinis” over the fence with neighbours whilst their children play happily in large gardens following a day of enriching educational activities and home baking sessions, is a far more easy and pleasant one than the very real hardship being experienced by many cooped up in cramped and inadequate accommodation, trying to juggle work and caring responsibilities, manage their own or a partner’s mental health issues or living in the shadow of abuse, all whilst trying to cope on 80% (if they are lucky) of an income that was never enough in the first place.

Increasingly, the national conversation is beginning to turn to when we might expect to see the restrictions eased and some semblance of normal life restored. There have been media reports that, during the Prime Minister’s absence recovering from what seems to have been a serious illness as a result of Covid-19 infection, the Cabinet is split between those Ministers who are advocating a swift return to normality in order to save the economy and those who counsel caution and remaining in lockdown until the medical and scientific advice points unequivocally towards a lifting of controls. Those media commentators hoping for a bullish response from the PM on his return must have been disappointed by the cautious and measured Boris Johnson who appeared in front of the cameras in Downing Street on the morning of his first day back at work https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-52439348

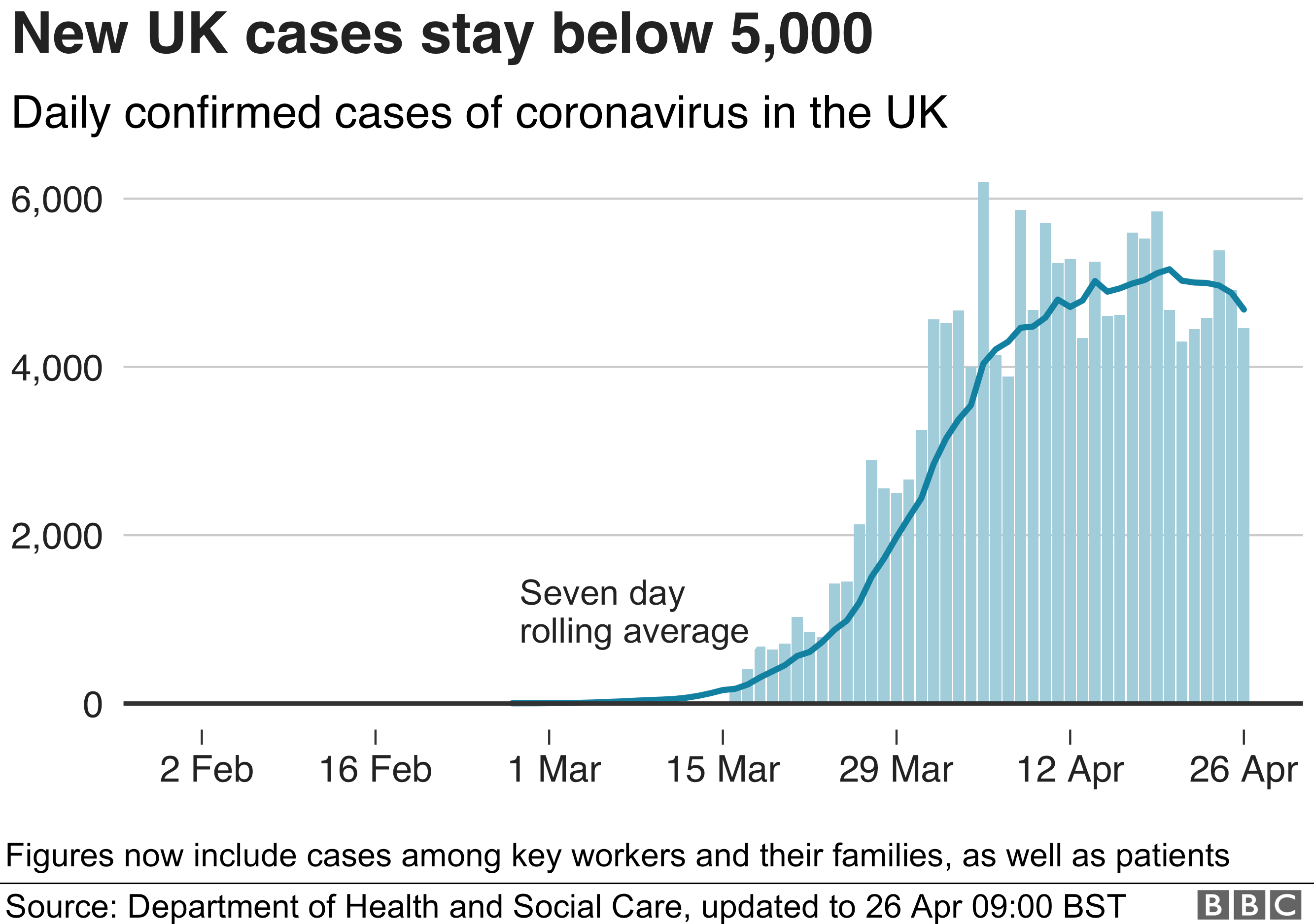

However fast or slow the exit from lockdown may be, the latest figures from the Department of Health do seem to suggest that both recorded new cases and deaths have passed the peak, even if there is no sign of a rapid descent down the curve.

It is clear that at some point, and possibly sooner rather than later if pressure continues to mount on the Prime Minister from business leaders and their parliamentary champions, the country will begin the transition back to normality, even this proves to be a slow process rather than a binary switch https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/22/uk-will-need-social-distancing-until-at-least-end-of-year-says-whitty

This is an appropriate time to reflect on what are the lessons and experiences from the past six weeks that we can take with us into the future.

One thing that is abundantly clear is that what has been referred to as the “global pause” is just that: nothing has fundamentally changed as a result of Covid-19, there has just been a temporary interruption to normal life. The world remains on track towards a disastrous level of global heating and the sixth mass extinction that has seen species and their habitats around the world vanish at an unprecedented rate continues unabated.

What this hiatus has done is give us a moment of enforced reflection to consider what is really important and how certain some of the old certainties are after all. Recent opinion polls in the UK show that the public want to see the Government tackle climate change with the same urgency as has been seen in its response to the coronavirus. This means that any recovery needs to be kickstarted by some form of green stimulus package – a nationwide programme of retrofitting the millions of homes that currently lack decent insulation, thus reducing carbon emissions and tackling fuel poverty would be a good start – rather than bailing out the oil companies and airlines. Certainly, having spent billions of pounds in propping up the economy, any return to the “there is no magic money tree” narrative will lack a certain amount of credibility, even if we have yet to see the obvious and almost inevitable corollary to increased levels of public spending, which is higher levels of taxation, being presented to the British public by a Conservative Chancellor. The switch of large amounts of manufacturing capacity over to making PPE and ventilators for the NHS, demonstrates how a comparable re-tooling and re-skilling could switch capacity in “dirty” industries to the products that will be needed for any Green New Deal – wind turbines, heat pumps and insulation, for example. The pandemic and the resulting global pause has brought us to a point where we can reassess what we want the future to look like. We can either opt for a return to business as usual or we can choose a path towards a different future, one in which nurses, delivery drivers and fruit pickers continue to be seen as key workers and valued accordingly; a future in which the working day does not need to be preceded and followed by an hour or more stuck in traffic or crammed into a standing room-only commuter train; a future in which our worth is determined by who we are rather than by what we own and one in which we value community and human contact all the more for having been forcibly deprived of them.

On the other hand, we can allow a Government, spurred on by the vested interests and corporate lobbyists, to repeat the mistakes of the “recovery” that followed the 2008 financial crash when the banks and other institutions whose mistakes a wrongdoing had caused the crisis were handed a bailout that was paid for by a decade of austerity inflicted on the most vulnerable in society and a freeze in public sector pay that slashed the living standards of the same people who are now being hailed as national heroes.

There is no getting away from the awfulness of the Covid-19 pandemic and its impact on people’s lives and livelihoods as well as the appalling number of lives lost. The challenge we now face as a society is how to construct a future that is a fitting memorial to those we have lost so that 2020 goes down in history as a key turning point in the history of humanity.